📞 Call Us On (0)333 123 0880

📦 Free Delivery for Orders over £25

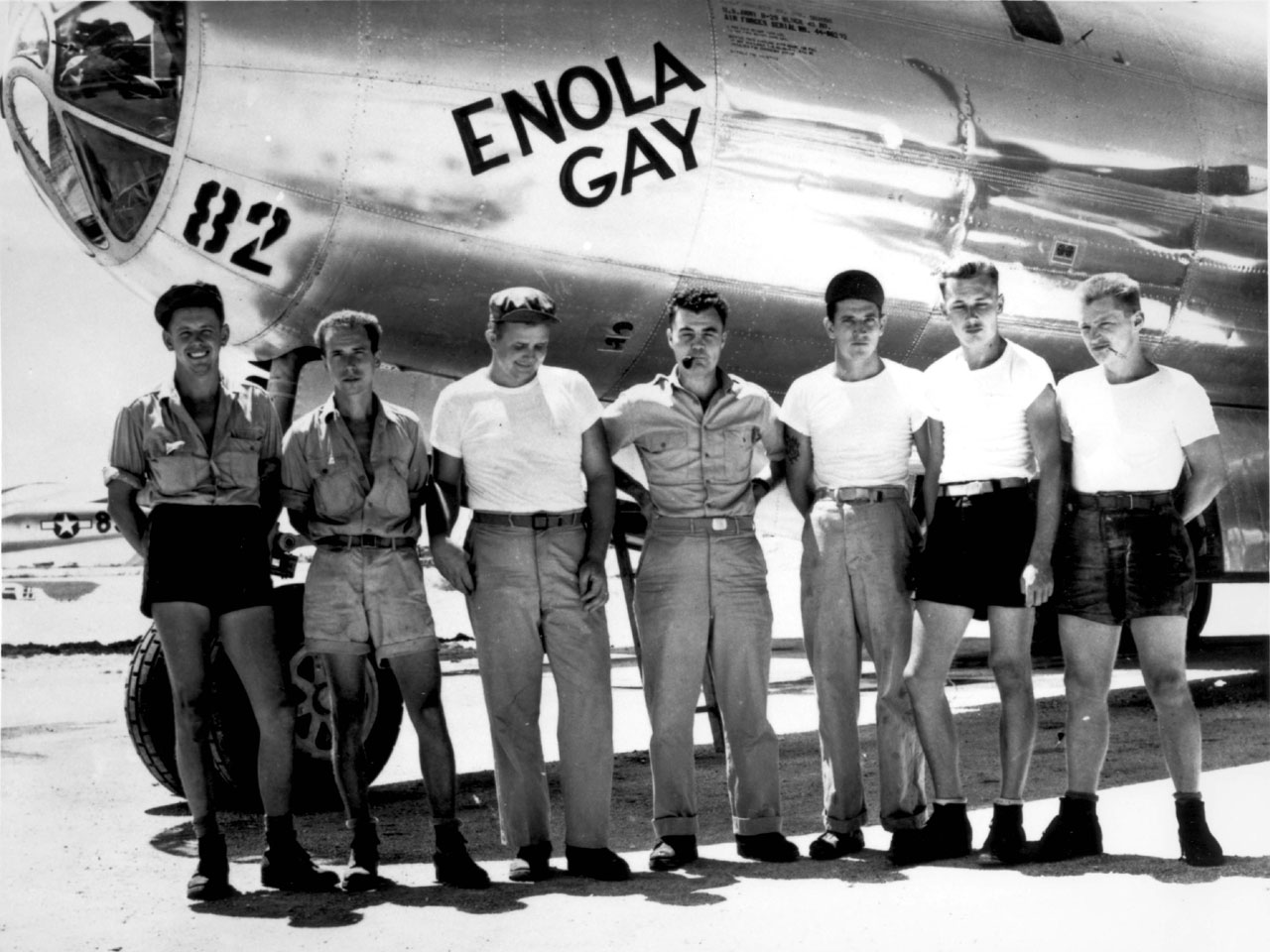

It is seventy years today that a B 29 bomber with two escorts dropped the first atomic weapon on the city of Hiroshima in Japan. The immediate death toll from the intense heat, the blast and the resulting fires it caused is estimated at 80,000. Three days later the city of Nagasaki was levelled in a second attack killing 40,000.

It is seventy years today that a B 29 bomber with two escorts dropped the first atomic weapon on the city of Hiroshima in Japan. The immediate death toll from the intense heat, the blast and the resulting fires it caused is estimated at 80,000. Three days later the city of Nagasaki was levelled in a second attack killing 40,000.

The radiation sickness from these bombs has continued to take its toll over the subsequent years, and official estimates put the death toll at 379,776.

And the human stories behind each of these numbers is tragic to read.

There were, and are, competing narratives about these attacks. The deaths of these "few" are considered small in comparison with the deaths that would have ensued if the US had to invade and conquer the Japanese islands. The immediate deaths by these weapons were moderate compared with a more conventional bombing raid on Tokyo five months earlier which killed 88,000 and injured 41,000. The use of these weapons forced the capitulation of a people with a "no-surrender culture", and the saving of up to a million American and Allied lives.

Criticisms of the bombings include the views that atomic bombing is fundamentally immoral, that the bombings counted as war crimes, that they were militarily unnecessary, that they constituted state terrorism, and that they involved racism against and the dehumanisation of the Japanese people. The strongest narrative in Japan is that the use of the weapons was prompted by geopolitical motives—a desire to prevent Russia invading and bringing Japan within it's own political orbit; that it was the first act of aggression in the Cold War.

These events continue to hang over our world, and its international politics, standing as a stark warning that kept the balance of power between East and West for 50 years. No one was in any doubt about the consequences of mutually assured destruction.

But how do we asses this painful and tragic event 70 years on? What can Christians say about the moral maze that has sprung up around what happened at 8.15 on the morning of 6th August 1945?

The Bible gives us a strong sense of two very different narratives at work in the world. The first is that God is sovereign over all of history. We believe and trust in a God who is at work in the world and bringing all things to a conclusion, and that everything is moving towards that one single point when Jesus returns. God does not cause evil. But somehow in his sovereign wisdom, even pain, suffering and evil will serve his ultimate purposes:

"To bring unity to all things in heaven and on earth under Christ." Ephesians 1 v 10

The other narrative is that of human responsibility. That in this fallen world, we remain responsible for our actions, and we will be judged for them on that great day—when all excuses and false justifications will fall away and all wrongs put right. It is a day to be welcomed, because it is a day when every injustice will be recognised and dealt with fairly and clearly, for everyone to see.

It troubled me deeply as a young believer that these two ideas seemed to be mutually exclusive. But as I have grown as a Christian I see more and more how liberating and exciting these truths are as two lenses through which to view the world. The swing point for me was seeing how these two truths converge in the death of Christ.

Jesus death is the ultimate example of how sin, pain and suffering can be God's means to bring rescue, delivery and peace.

"You intended to me harm, but God intended it for good," said Joseph to his brothers (Genesis 50 v 20). Jesus "was handed over to you by God’s deliberate plan and foreknowledge; and you, with the help of wicked men, put him to death," said Peter on the day of Pentecost (Acts 2 v 23). And the Lord himself said to his disciples:

"The Son of Man will go just as it is written about him. But woe to that man who betrays the Son of Man! It would be better for him if he had not been born.” Mark 14 v 21

Jesus death is the ultimate example of how sin, pain and suffering can be God's means to bring rescue, delivery and peace.

How far we can apply these truths to everything that happens in history and our lives is hotly debated among believers, but these two truths surely give us strong guidelines for how we respond:

Now you've read the article, let us know what you think. Comment in the box below. You can also like us on Facebook, follow us on Twitter, and subscribe to our YouTube Channel